Historical Development

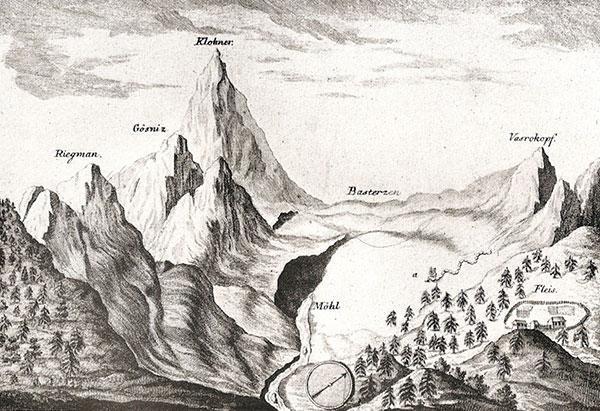

It is the 3rd century BC. A time that is actually not easy to grasp. What did it look like back then? We do not know. What we do know is that the first records of Heiligenblut am Grossglockner date back to this time. Around 400 BC, the Taurisker or Celts arrived in the area. The term "Tauern" supposedly comes from them.

Agriculture and livestock farming kept these people busy and they were already searching for the famous Tauern gold. The Romans built the first roads over the mountains around Heiligenblut and the first connections to the north were established as early as 15 BC. The Romans were so good at building roads that some of the roads of that time are still part of the most famous Alpine passes today.

.png)