Historical Development

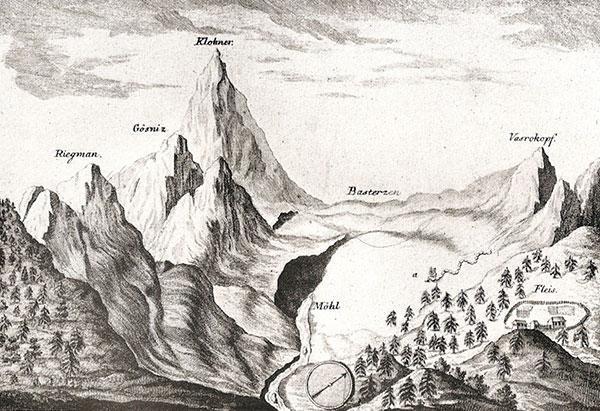

Imagine, if you will, the year 300 B.C. An era that is challenging to grasp from a modern perspective. What did the world really look like back then? None of us can know for sure. What we do know is that this is when Heiligenblut am Grossglockner was first mentioned in a written document; we also have evidence that, in around 400 BC, the Celts moved into this area – also called the ‘Tauriscans’. This is where the name of the ‘Tauern’ mountains is believed to have originated.

Agriculture and animal husbandry were at the centre of people’s lives, though the Celts also went in search of the well-known Tauern gold. A few centuries later, the Romans built the first pathways over the mountains around Heiligenblut, establishing the first north-bound connections as early as 15 BC. In fact, they were such skilled road builders that some of today’s most well-known mountain passes have incorporated parts of these ancient Roman routes.

.png)